a secular temple?

It is so tempting to give up on religion. When faced with the frustrating, if not horrific, ways in which religions are exploited in order to dehumanize others, maintain power and control, and repress our own inner chaos, it’s no surprise that many have tossed their faith on the rubbish heap. What was meant to help us overcome evil has often become a tool, perhaps even a cause, of evil.

This is, of course, not new. For similar reasons many Europeans did exactly this generations ago – tossing aside their violence-strewn faith in the hope of developing a humane and thoughtful secular approach. The French, in particular, added passion to this hope for laïcité, a secular space free from religious domination and control.

Somewhat uniquely, they even dedicated a huge “secular temple” in Paris, known as the Panthéon. Originally built in the late 18th century to be a church dedicated to St. Genevieve, patron saint of Paris, the French Revolution (and more revolutions since) interrupted the process. After some back and forth over the decades, the end result has been a temple dedicated to the “great men” of France (“gods” even less inspiring of worship than the Roman gods for which the Pantheon in Rome was built millennia earlier – a Pantheon whose history has been the reverse, being built as a temple to all the gods and becoming consecrated as a Christian church in the 6th century).

Visiting the Panthéon in Paris a couple of weeks ago, I was struck by the way in which this huge edifice is simultaneously awesome and lifeless. Nearly cleansed of religion (a Christian mosaic remains above the “altar” and a cross remains atop the dome as an odd relic of a pointless compromise), it is a massive mausoleum with around 77 bodies or memorial sites in its crypt.

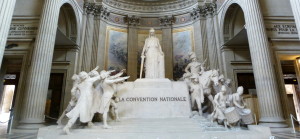

It’s not new for me to visit large churches or cathedrals that have felt empty and lifeless, but nothing compared to this. Ironically, in what is intended to represent humanistic values, it feels so deprived of the human. There are no prayers being said, no songs being sung. It inspires no struggling community of faithful who gather over potlucks. And it’s hard to imagine the altar to “La Convention Nationale” (the assembly created by the French Revolution) inspiring much of anything at all – and I believe I would say the same if I were French.

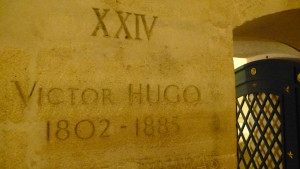

One of the best known heroes buried in the Panthéon was Victor Hugo, beloved author of Les Miserables. His deep love for humanity’s triumph over all the dehumanizing tendencies within all systems of power, be they religious or not, led to millions of Parisians marching in his funeral procession to the Panthéon. Hugo was harshly critical of the Church for its stubborn clinging to medieval values and its refusal to care more for the masses crushed by poverty. So it is not wrong that he is connected with the Panthéon’s attempt to celebrate something greater and more life-giving than the church of his day.

But it has failed. Instead the Panthéon now demonstrates that a secular temple is not the solution to the many flaws found within religious institutions. We need a faith that can inspire. We need stories that feed the spirit, and we need communities that gather to celebrate, redeem and nurture. There is so much that is wrong at present in churches (and mosques, synagogues and temples), but it’s hard to be optimistic about a future that abandons the attempt to come together somehow, intentionally, in communities that feed the spirit. We must throw ourselves into transforming our practices of faith rather than abandoning them.

Victor Hugo wrote in Les Miserables:

In this nineteenth century, the religious idea is undergoing a crisis. People are unlearning certain things, and they do well, provided that, while unlearning them they learn this: There is no vacuum in the human heart. Certain demolitions take place, and it is well that they do, but on condition that they are followed by reconstructions.

Hugo lies buried in a sterile building that demonstrates that this reconstruction is not easy. It’s hard to imagine that there is a completely secular path to the kind of reconstruction he urged. Secularism helps to create a safe, public meeting place, but we must do better at transforming our faith practices if we don’t want empty and lifeless secular temples to be all we have left.

Nice thoughts; very thought-provoking; thanks Walter.

This would be better discussed over coffee or wine, but let’s try these comments for now.

My thoughts which follow are very undeveloped thoughts, and I’m keen to hear your responses if you want to have a bit of a back and forth.

—

So, in the context of this blog post (or, if you prefer, more widely/broadly 🙂 ), how do you define religion? Is agnostic uncertainty a religion, or does one need to hold a particular conviction [i.e. association with one of the ‘world’s religions].

Because it strikes me that some ‘non-religious’ places (maybe different than ‘secular’ places…depending on how we define religion/secular I suppose) are very spiritual places………….does “religion” require a Being who listens to/hears the prayers/songs (alluded to in paragraph 5).

—

You can ask me to clarify/expand if nothing I’ve said yet makes sense/prompts a reply.

I think ‘in the context of this post’ (lest I pretend to be too universal) I was thinking of religion as “shared faith practices intentionally engaged in by a gathered community.” In that sense I wouldn’t think of “agnostic uncertainty” as a religion, though it would, in my opinion, be a very health aspect/attribute of a religion. I think the complete absence of some consciously agnostic uncertainty is a key mark of unhealthy religion. And, I don’t think “association with one of the world’s religions” is a part of my definition, assuming that implies the institutional aspects of the major religions. This is related to a dilemma which I may comment on below separate from this reply. Yes, I can see how ‘non-religious’ places might be very spiritual – I think what struck me was precisely how much this was not true of the Pantheon, which seemed almost spirit-quenching to me. Might a non-religious spiritual place actually inspire the beginnings of spiritual/religious responses in people, which become somewhat shared and intentional (and, hence, closer to my definition of religion as opposed to spiritual)?